Héraldique

Héraldique

Scaricamazza

·1723·

Scaricamazza

·1723·

Quando è nata l'araldica?

Quando è nata l'araldica?

Saremo sintetici: l’araldica nasce intorno al 1150. Spieghiamo. Fin dal Medioevo sono state avanzate diverse ipotesi: già nel 1671 padre Claude-François Ménestrier ne elenca venti nella sua opera Le Véritable art du blason et l’origine des armoiries. Alcune tesi sono alquanto bizzarre – attribuiscono l’invenzione delle armi ad Adamo o a Re Artù, per esempio -, altre sono più plausibili e per questo hanno avuto una vita più lunga, una maggiore influenza; un neofita che non abbia letto nulla di araldica potrebbe considerarle corrette e abbracciarle ciecamente.

Stemma di Dardanus, figlio di Zeus, primo re di Troia. Fonte: Ehrenspiegel des Hauses Österreich (1500-1555). Le armi attribuite sono stemmi dell’Europa Occidentale dati retrospettivamente a persone reali o fittizie che morirono prima dell’inizio dell’era dell’araldica, nella seconda metà del XII secolo.

Le tre teorie predilette dagli araldisti del passato giunte fino a noi, ma che gli storici oggi hanno scartato, sono: I, gli stemmi non sono altro che la continuazione delle armi familiari e militari dell’antica Roma e della Grecia;

Hoplite wearing his shield, the “aspis”, with a dog decoration. Attic red-figure eye-cup, 500–490 BC. From Chiusi, Italy.

Museo Archeologico Regionale Antonio Salinas, Palermo, Sicily, Italy.

II, alla base degli stemmi vi sarebbero le insegne barbariche dei popoli germanici, slavi e scandinavi;

Ax Head. Scandinavian. 11th–12th century. Decorated weapons – swords, axes, spears – were the most highly valued possessions of Viking men, essential as symbols of their rank and status within society, in addition to serving as functional fighting equipment. Metropolitan Museum of New York.

III, l’araldica ebbe origine in Oriente: gli occidentali adottarono emblemi orientali, bizantini o musulmani, durante le Crociate; è la teoria più antica. Per quanto affascinanti i fatti storici dimostrano che le teorie in questione non possono più essere accettate. Ad esempio, all’epoca della prima crociata le armi non esistevano; sembrano essere state usate solo nella seconda. Stephen Slater, nel 2004, ci ricorda:

«Thirty years after Duke William’s victory at Hastings [14 October 1066] the Byzantine Princess Anna Comnena (1083-1148) was casting her curious and careful eye over the shields of the Frankish knights who were passing through Byzantium on their way to join in the First Crusade. In the Alexiad, her journal of those far-off times, the princess mentions with much admiration that the shields of the Frankish knights were “extremely smooth and gleaming with a brilliant boss of molten brass”, yet the account si most interesting for what ti makes no mention of – any suggestion of personal devices or patterns such as those we describe by the term “heraldry”».¹

Già nel 1845, Mark Antony Lower, scriveva:

«A proof that regular heraldry was unknown at the era of the Conquest, is furnished by that valuable monument, the Bayeux Tapestry, a pictorial representation of the event, ascribed to the wife of the Conqueror. In these embroidered scenes neither the banner nor the shield is furnished with proper arms. Some of the shields bear the rude effigies of a dragon, griffin, serpent or lion, others crosses, rings, and various fantastic devices; but these, in the opinion of the most learned antiquaries, are mere ornaments, or, at best, symbols, more akin to those of classical antiquity than to modern heraldry. Nothing but disappointment awaits the curious armorist, who seeks in this venerable memorial the pale, the bend, and other early elements of arms. As these would have been much more easily imitated with the needle than the grotesque figures before alluded to, we may safely conclude that personal arms had not yet been introduced. Dallaway asserts that, after the Conquest, William “encouraged, but under great restrictions, the individual bearing of arms;” but, strangely, does not cite the most slender authority for the assertion. Camden and Spelman agree that arms were not introduced until towards the close of the eleventh century, which must have been within a very short time of the Conqueror’s death. Others again, with more probability, speak of the second Crusade (A.D. 1147) as the date of their introduction into this country. But even at this period the proofs of family bearings are very scanty. Traditions, indeed, are preserved in many families, of arms having been acquired during this campaign, and in a future chapter several examples will be quoted, rather as a matter of curiosity than as historical proof; for all tradition, and especially that which tends to flatter a family by ascribing to it an exaggerated antiquity, will generally be found to be vox et preterea nihil. The arms said to occur on seals in the seventh and eighth centuries may be dismissed as merely fanciful devices, having no connexion whatever with the heraldry of the twelfth and thirteenth. Towards the close of the twelfth century, and at the beginning of the thirteenth, A.D. 1189-1230, it was usual for warriors to carry a miniature escocheon suspended from a belt, and decorated with the arms of the wearer».²

Se, ora, siamo più convinti che l’araldica non è anteriore al XII secolo, perché possiamo trovare figure e motivi che decoravano scudi e tessuti e che ricordano sia emblemi greco-romani che barbarici, germanici, scandinavi, slavi e orientali? La ragione va ricercata in quella differenza tra segno, emblema ed emblema araldico; una differenza illustrata nella nostra prima lezione: “Cos’è l’araldica?“. Gli uomini del Medioevo crearono un nuovo sistema emblematico, l’araldica; non l’hanno ereditato. Tuttavia, per farlo, utilizzarono oggetti (lo scudo, i tessuti), simboli, motivi, segni, figure del loro patrimonio.

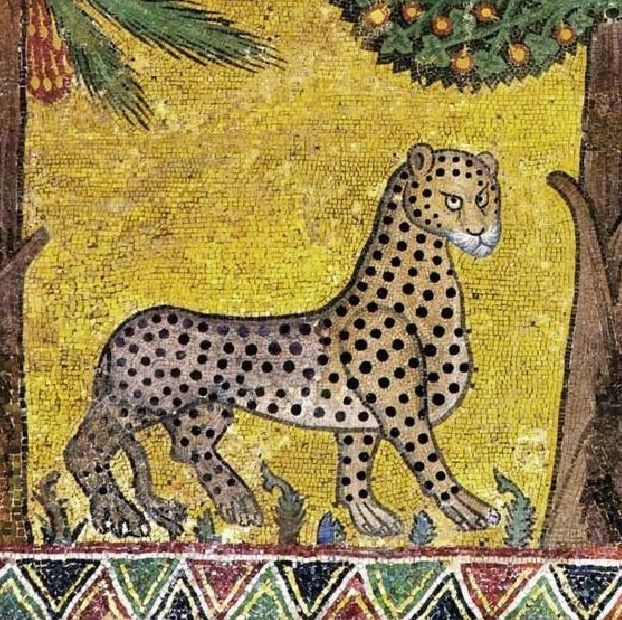

The Palazzo dei Normanni (Norman Palace), Sicily, Italy. King Roger’s Room: mosaics of the room commissioned by King Roger II of Hauteville (1095-1154).

¹Slater, S. (2004). The History and meaning of heraldry. An illustrated reference to classic symbols and their relevance, 1st edn, London: Southwater, p.8.

²Lower, M.A. (1845). The Curiosities of Heraldry, 1st edn, London: John Russell Smith, pp.19-20.

Questo era affollato di animali esotici, di segni magici, simbolici o allegorici carichi di significato. Erano orientali, greci, romani o barbari. A volte, però, queste stesse figure o caratteristiche geometriche erano semplici strumenti per distinguere se stessi e il proprio gruppo da un altro. L’araldica era appena agli inizi ma era già ricca di segni, animali e fascino sfuggenti. Allora perché l’araldica nasce intorno al 1150? Stavamo rispondendo al quando, non è vero? Per rispondere a questa seconda domanda, miei cari, abbiamo bisogno di un’altra lezione.