Héraldique

Héraldique

Scaricamazza

·1723·

Scaricamazza

·1723·

When did heraldry begin?

When did heraldry begin?

We are synthetic: heraldry born around 1150. Let’s explain. Since the Middle Ages, various hypotheses have been proposed: already in 1671 Father Claude-François Ménestrier lists twenty of them in his work Le Véritable art du blason et l’origine des armoiries. Some theses are quite bizarre – they attribute the invention of weapons to Adam or King Arthur, for example – others are more plausible and for this reason have had a longer life, a greater influence; a neophyte who has read nothing about heraldry might consider them correct and embrace them blindly.

Coat of arms of Dardanus, son of Zeus, first king of Troy. We can see some attributed arms. Attributed arms are Western European coats of arms given retrospectively to persons real or fictitious who died before the start of the age of heraldry in the latter half of the 12th century. Source: Ehrenspiegel des Hauses Österreich (1500-1555).

The three theories favored by heraldists of the past, which have come down to us but which historians today have discarded, are: I, coat of arms are nothing other than the continuation of the family and military emblems of ancient Rome and Greece;

Hoplite wearing his shield, the “aspis”, with a dog decoration. Attic red-figure eye-cup, 500–490 BC. From Chiusi, Italy.

Museo Archeologico Regionale Antonio Salinas, Palermo, Sicily, Italy.

II, at the base of the coats of arms there would barbarian insignia of Germanic, Slavic and Scandinavian peoples;

Ax Head. Scandinavian. 11th–12th century. Decorated weapons – swords, axes, spears – were the most highly valued possessions of Viking men, essential as symbols of their rank and status within society, in addition to serving as functional fighting equipment. Metropolitan Museum of New York.

III, heraldry originated in the East: Westerners adopted Eastern emblems, Byzantine or Muslim, during the Crusades; it’s the longest-standing theory. However fascinating the historical facts demonstrate that the theories in question can no longer be accepted. For example, arms did not exist at the time of the first Crusade; they were established by the time of the second. Stephen Slater, in 2004, reminds us:

«Thirty years after Duke William’s victory at Hastings [14 October 1066] the Byzantine Princess Anna Comnena (1083-1148) was casting her curious and careful eye over the shields of the Frankish knights who were passing through Byzantium on their way to join in the First Crusade. In the Alexiad, her journal of those far-off times, the princess mentions with much admiration that the shields of the Frankish knights were “extremely smooth and gleaming with a brilliant boss of molten brass”, yet the account si most interesting for what ti makes no mention of – any suggestion of personal devices or patterns such as those we describe by the term “heraldry”».¹

Already in 1845, Mark Antony Lower, wrote:

«A proof that regular heraldry was unknown at the era of the Conquest, is furnished by that valuable monument, the Bayeux Tapestry, a pictorial representation of the event, ascribed to the wife of the Conqueror. In these embroidered scenes neither the banner nor the shield is furnished with proper arms. Some of the shields bear the rude effigies of a dragon, griffin, serpent or lion, others crosses, rings, and various fantastic devices; but these, in the opinion of the most learned antiquaries, are mere ornaments, or, at best, symbols, more akin to those of classical antiquity than to modern heraldry. Nothing but disappointment awaits the curious armorist, who seeks in this venerable memorial the pale, the bend, and other early elements of arms. As these would have been much more easily imitated with the needle than the grotesque figures before alluded to, we may safely conclude that personal arms had not yet been introduced. Dallaway asserts that, after the Conquest, William “encouraged, but under great restrictions, the individual bearing of arms;” but, strangely, does not cite the most slender authority for the assertion. Camden and Spelman agree that arms were not introduced until towards the close of the eleventh century, which must have been within a very short time of the Conqueror’s death. Others again, with more probability, speak of the second Crusade (A.D. 1147) as the date of their introduction into this country. But even at this period the proofs of family bearings are very scanty. Traditions, indeed, are preserved in many families, of arms having been acquired during this campaign, and in a future chapter several examples will be quoted, rather as a matter of curiosity than as historical proof; for all tradition, and especially that which tends to flatter a family by ascribing to it an exaggerated antiquity, will generally be found to be vox et preterea nihil. The arms said to occur on seals in the seventh and eighth centuries may be dismissed as merely fanciful devices, having no connexion whatever with the heraldry of the twelfth and thirteenth. Towards the close of the twelfth century, and at the beginning of the thirteenth, A.D. 1189-1230, it was usual for warriors to carry a miniature escocheon suspended from a belt, and decorated with the arms of the wearer».²

If we are now more convinced that heraldry is not prior to the twelfth century, why can we find figures and motifs that decorated shields and fabrics and that recall both Greco-Roman and barbarian, Germanic, Scandinavian, Slavic and Oriental emblems? The reason must be sought in that difference between a sign, an emblem, and a heraldic emblem; a difference illustrated in our first lesson: “What is heraldry?”. The men of the Middle Ages created a new emblematic system, heraldry; they did not inherit it. However, to do so, they used objects (the shield, fabrics), symbols, motifs, signs, figures from their heritage.

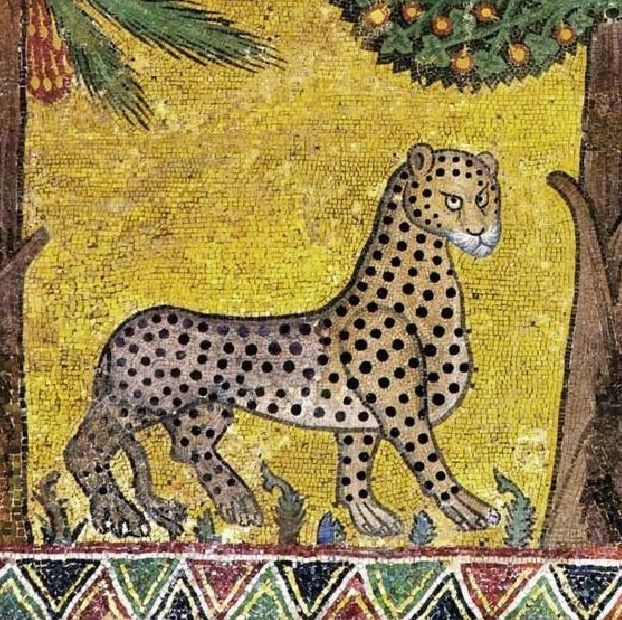

The Palazzo dei Normanni (Norman Palace), Sicily, Italy. King Roger’s Room: mosaics of the room commissioned by King Roger II of Hauteville (1095-1154).

This was crowded with exotic animals, magical signs, symbolic or allegorical, full of meaning. These were oriental, Greek, Roman or barbarian. Sometimes, however, these same figures or geometric features were simple tools to distinguish oneself and one’s group from another. Heraldry was just starting but was already full of elusive signs, animals and charm.

So why was heraldry born around 1150? We were answering the when. To answer this second question, my dear, we need another lesson.

¹Slater, S. (2004). The History and meaning of heraldry. An illustrated reference to classic symbols and their relevance, 1st edn, London: Southwater, p.8.

²Lower, M.A. (1845). The Curiosities of Heraldry, 1st edn, London: John Russell Smith, pp.19-20.